Paul Gough

Bristol School of Art, Media and Design, University of the West of England

Summary

I recognize; you recognize; we recognize; they recognize. Reconnaissance is concerned with familiarization, ridding ourselves of doubt, eschewing ambiguity. In addition to its customary military use – gathering intelligence about the disposition of enemy forces - reconnaissance is usually understood as a preliminary inspection of a given area so as to obtain data concerning geographic, hydrographic, or similar information. It is usually the prelude to a detailed or full survey. One of the more obscure origins of the term ‘ambiguous’ also locates it in the world of the military: ambiguity is a military term that means to be attacked from two sides at once.

This short paper examines an approach to drawing that is both exploratory – a line quite literally taken on a walk into an unknown place – but which attempts to record that journey by the most restrictive, even severe graphic line, a line that thrives on (indeed, insists on) un-ambiguity.

Introduction

One finds it in the midst of all this as hard to apply one’s words as to endure one’s thoughts. The war has used up words; they have weakened, they have deteriorated … (Henry James 1915)

Throw your India rubber away.

-

A line should be as sharp and precise as a word of command.

A wavering line which dies away carries no conviction or information because

it is the product

of a wavering mind. Every line should be put in to express something. Start sharply and finish sharply. Press on the paper.

(William Newton 1915: 27)

Published in TRACEY the online journal of contemporary drawing research, September 2006 http://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/ac/tracey/

However, the collapse of the written word was matched by the emergence of a pictorial language that attempted to first calibrate then codify the destruction of the European battle zones. It was given the somewhat inelegant moniker of ‘military sketching’. In the west, the military have long used drawing as a navigation and exploratory tool. From the early 18th century, British military academies trained gentlemen cadets and junior sailors to analyse and record landscape and coastline with the aim of neutralizing and controlling enemy space. Many highly regarded artists have been instructed in the military sketch. Whistler, while at West Point, learned the craft of ‘breaking ground’ through painstaking analysis, calm measurement, and a slow rendering of a distant landscape. (Gough 1995)

At the heart of military observation is the painstaking process of panoptic scrutiny. Seeing is about power; and the omnipresent eye is concerned with absolute power. As Ernst Junger (1937) wrote:

-

It is the same intelligence, whose weapons of annihilation

can locate the enemy to the exact second and metre, that labours to preserve

the great

historical event in fine detail.

Like sniping, military sketching could be taught. Within a few years of the establishment of the first military academy at Woolwich in 1741, a drawing master had been appointed and the Gentlemen Cadets were set lessons in 'Sketching Ground, the taking of Views, the drawing of Civil Architecture and the Practice of Perspective'. (Buchanan 1892: 33) During the 18th and 19th centuries the military academies at Woolwich, Dartmouth, and later Sandhurst and Marlowe, attracted many artists of renown. Paul Sandby, David Cox and Alexander Cozens all taught the rather tedious business of ‘breaking ground’, although many of Sandby’s pupils went on to become noteworthy landscapists in the picturesque manner. (Hardie 1965)

John Constable, however, rejected the offer of a post in 1802 remarking that had he accepted 'it would have been a death blow to all my prospects of perfection in the Art I love.' (Constable 1802) For all its attractions – in particular, a career with good remuneration - military sketching was regarded with some disdain, a process of 'tame delineation', of reducing the aesthetics of nature to something ordinary or (to borrow Gainsborough's dismissive phrase) something 'mappy'. For others, the task of 'breaking ground' and issuing a neutral report was, like the very term 'military intelligence', a contradiction in terms. However, for some time before the establishment of the Royal Academy, the only formal tuition in drawing lay in the weekly classes at the military academies.

Two fields of vision

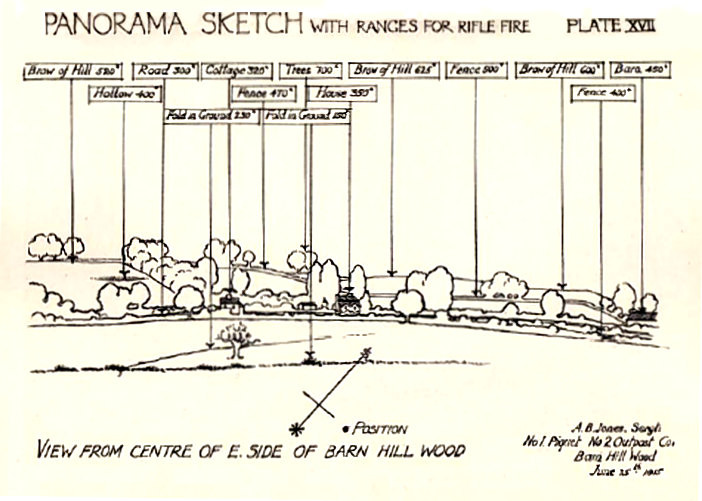

Drawing for military purposes has two distinct fields of vision: information-drawings gathered during mobile reconnaissance (usually by peripatetic patrol) and drawings made from fixed positions usually from some place of elevation. These drawings are invariably panoramic in style, and customarily the preserve of the artillery spotter (a gunner in a concealed position far forward of the battery).

Where the patrol sketch is often a collage of hasty impressions later re-arranged to form a sequential narrative, the panorama is primarily concerned with scopic control and spatial dominance. The artillery panorama works on the same premise as military mapping. It assumes that surveillance and graphic survey will eventually neutralise a dangerous terrain and assure mastery over it. (Alfrey and Daniels 1990)

If the ambition was to gain a total, unimpeded gaze, it was far from easy to achieve. In Foucaultian terms, such a vantage would lead to absolute dominance, delivering a system of permanent registration such as that which operated in the plague towns in the 17th century, where every movement was recorded, every circumstance encoded.(Foucault 1977) On the set piece battlefields of the Napoleonic era, and on the septic terrain of the First World War the panoramic drawing became an integral part in segmenting and immobilising perceived space. During the Great War, the stasis of the battle line, however, meant that the panoptic ideal could never be attained: dead ground (space beyond or concealed from retinal view), camouflage and concealment were constant frustrations to retinal surveillance. Foucault's concept of a transparent space was constantly frustrated by the fissured and volatile landscape of the battlefield. The military sketch, though, provided the nearest graphic proof of Bentham's paradigm: systematic observation 'in which the slightest movements are supervised, in which all events are recorded.’

Graphic trace

Achieving scopic control could be taught. Since the mid 19th century a succession of training manuals have been produced by the Armed Services. During times of conflict commercial publishers also created ‘simple’ drawing guides and manuals for mapreading, panorama and field sketching. Official or commercial, the language was invariably clipped and precise:

-

It may be premised that, from a military point of view,

it is not necessary to be an artist to produce a useful panorama. Indeed,

it is better almost that the artistic

sense should be absent, and that instead of idealising a landscape, it should be looked at with a cold, matter-of-fact eye. Thus the sketcher would note rather the

capabilities of the country for military purposes than its beauties of colouring or the artistic effects of light and shade.

(War Office 1914)

-

A line should be as sharp and precise as a word of command.

A wavering line which dies away carries no conviction or information because

it is the product of a

wavering mind. Every line should be put in to express something. Start sharply and finish sharply. Press on the paper.

(Newton 1916: 27)

Figure 1  |

By thus ridding the page of ambiguity or doubt, the drawings aim to control distant (and desirable) space and so pre-ordain the future. This segues easily into the written word, which uses the active and instructive tense of military command as its basis. It is a language where the passive or conditional does not function: 'Brigade will commence at ..., Objectives shall be taken by ..., reinforcements will be moved to ... etc'. (Keegan 1976:266) Maps and charts drawn up before offensives use a similar code; barrage lines are clearly marked in minutes of advance. In June 1944 the objectives beyond the

Normandy beachhead were marked out in time - D Day plus one, plus two, etc - as well as in actual space.

The panorama, though, could only make sense in a war where both sides were predominantly static, where a battlescape was shared but where the zones of control were clearly demarcated. The view from the opposing emplacements might be radically different but the contested ground was rationalised and systematised using a shared vocabulary of grid and line. In his analysis of the tourisms of war, Jean Louis Deotte, has argued that the beachline of Normandy in 1944 constituted a common world, a shared objectivity for both defender (cooped in a concrete pillbox) and attacker (exposed in a tin landing craft). Both sets of adversaries experienced a 'reversibility of the points of view' because 'enemies share in common the same definition of space, the same geometric plane ... they belong to the same world of techno-scientific confrontation, the substratum of which, here, is sight'. (Diller and Scofidio 1994: 116 - 177)

‘A line which dies away…’

The actual language of military drawing has little variety or range. What is instantly evident in the illustrations in the training manual is that contour and outline is preferred, shade is not permitted unless it draws the eye to salient points of tactical value. Foreground information is of no value to the artillery spotter who focuses only on the distance; by comparison reconnaissance drawings slip often into map-making, sharing some of its diagrammatic conventions and symbols: a pine plantation is indicated by a simple perimeter edge ‘filled in’ with one or two ‘conifer’ icons. Easy to learn by the novice, the conventions were less easy to adapt by professional artists who found themselves conscripted into survey regiments, or scouting sections in the infantry. Vorticist painter William Roberts remembered his first (and only foray) into reconnaissance drawing in the First World War:

-

From the OP (Observation Post) I saw a completely featureless

landscape, save here and there a few broken sticks of trees. I made a

pencil drawing of this barren

piece of ground, but what use my superiors would be able to make of this sketch I could not imagine.

(Roberts 1974: 27 - 28)

A very different artist, who felt that it was not enough to entrust military drawing to bemused avant garde painters, was the subaltern William Newton. A trainee architect, Newton put forward the proposition that it was possible to teach a novice how to draw a battle landscape after just one lecture and two days drawing in the open. He laid out his ideas in a manual - Military Landscape Sketching and Target Indication - published commercially in 1916. (Newton 1916)

In the preface his commanding officer summarized the method: The test of each solution is whether a stranger can with ease and rapidity identify the exact place intended; and tested in this manner the results of his teaching have been most successful and many officers in the trenches have benefited by the care and devotion he has given to his work. (Newton 1916: 6)

Newton clarified the function of a military sketch, as:

-

'a form of report, without the ambiguity of language.

It is graphic information. For information clearness is essential, and

clearness is attained by two avenues:

a) thought, b) draughtsmanship'.

(Newton 1916 : 6)

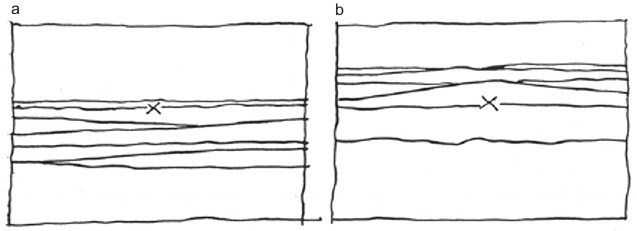

Figure 2 Newton: Seperation into Planes  This can be indicated by drawing the planes. Note the difference in the apparent positions of 'X' in diagrams (a) and (b) |

Possibly the most interesting of these three methods is the first - the ‘separation of planes’. Newton suggests that the draughtsman should try to imagine a landscape as a series of horizontal (but not necessarily straight) bands that stretch from one side of the paper to the other. (Figure two) It might help to imagine the country as something like the scenery of an outdoor exhibition with each ridge, hill, wood cut out of sheets of wood and laid one behind the other. Having done this, a point can successfully be marked on the drawing, its approximate distance from the viewer clearly indicated by the number and density of horizontal lines representing fields, meadows, tree lines in between the draughtsman and the point.

Newton's manual teems with such practical advice. He emphasises the draughtsman's duty in guiding the eye to the most urgent points in the landscape by using key devices already in the terrain - a single red roof amongst black ones, an isolated chimney, three silhouetted bushes on a crest line – treating them as so many labels that indicate particular targets or tactically vital features. He avoids the tendency of other instructors to construct complex drawing frames, or string and protractor gizmos. (Green,1908: 25) Instead, he argues for clarity of purpose at all times, for always using a sharp pencil and throwing the india rubber away - 'the aim should rather be to do a clear sketch from the first, because in the field opportunities of subsequent polish are limited'. Such instruction may sound a little severe, even archaic, but it was born from a belief in the superiority of careful observational drawing as a method of study and analysis. Without the rigorous discipline advocated by Newton, military drawing can easily descend into a parody of itself - dull, repetitive diagrams in which trees have been reduced to a formula, producing a landscape image that resembles 'nursery wall paper'. This was due in part to the consequences of drawing copses and woods in outline, which tends to make them resemble their cartographic equivalent - either bushy topped

deciduous or 'Christmas tree' firs. It is also the consequence of drawing in outline alone and so accentuating the top line of trees and buildings with a minimum of shading and colour.

Newton’s methods achieved instant familiarity, a place of danger was rid of its doubt, ambiguity was eradicated. Drawing had become function. However, it is not surprising – given the number of professional artists working for the armed services in the Great War – that an aesthetic began to emerge. Many military drawings began to resemble the arts and crafts style woodcut illustrations that were popular in the first decades of the century.

The Studio magazine was quick to note the similarity. In February 1916 an illustrated article applauded the army's work in broadening the education of the common soldier, noting with pleasure that 'instruction has been extended to the rank and file because the authorities recognise the immense value on active service of men who can use a pencil in making topographical sketches'. (‘R.F.C.’ 1916: 44 - 45) The writer marveled at how such a short period of instruction could produced occasionally elegant pieces. Proof perhaps that 'one can just as easily be taught to draw the formation of objects in nature as to trace the design of the letters of the alphabet'. Faint (but clearly audible) praise was landed on soldier’s efforts:

These sketches are, of course, not intended to be artistic in their handling, but at

the same time there is a certain charm in their simplicity, and the conventional

method does not detract from their interest. (‘R.F.C.’ 1916: 45)

In the era of GPS and digital surveying, drawing for military purposes might be considered a quaint or antiquated habit. Far from it. Not only were soldiers trained to draw in the Second World War, the skill is still maintained in the regiments of Royal Artillery in the British army, whose Forward Observation Officers augment their map work with neat outline drawings made in non-permanent marker pens onto small sheets of acetate. However perfunctory the actual image might seem, the dominant features of the distant terrain are firmly seen and drawn, the line is unwavering and rid of any ambiguity, the purpose is entirely clear.

Coda – ‘zero trees’

Drawing is indeed a robust and vital form. Anthony Swofford’s scathingly honest narrative of the First Gulf War Jarhead, is the bleak account of his combat role with a US Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) platoon in Iraq. In an intensely close partnership, he and his spotter worked side-by-side deep in enemy terrain, the spotter’s scope just behind the shooter’s right elbow, his left leg draped over the shooter’s right leg. Swofford considers whether it is the spotter’s job that is actually more demanding – he must acquire the target, assist the sniper in locating it, figure the distance, estimate the wind and compute the co-ordinates, and then ‘call the shot’. It is, however, always the sniper who is credited with the kill.

Yet, even here there is an echo of the past:

-

‘Well before the shot is taken, the spotter will

have drawn a field sketch, so that distance is easily estimated and the

target rapidly acquired. The spotter might

say to the shooter, “Officer without insignia, directing troop movement. Three o’clock from the stand of trees.” Of course, in the Desert we anticipate exactly zero

trees in our field sketches. We assume our points of origin will be the burnt hulks of personnel carriers and tanks and the occasional gentle rise of the desert.

(Swofford 2003: 135)

I have been working on this subject for over a decade, ever since devising and presenting a thirty minute television documentary on military sketching. Fuller published accounts of the history and current uses of field sketching are in the following texts: Paul Gough (1995) 'Tales from the Bushy-topped Tree: a brief survey of military sketching' in Imperial War Museum Review, No.10, pp 62 – 74, and: ‘Dead Lines: Codified Drawing and Scopic Vision’Point: Art and Design Research Journal, Autumn/Winter, No.6, 1998 pp 34 - 41 ISSN 1360 3477. A further elaboration of the material culture of the ‘military sketch’ was given at the symposium Materialities and Cultural Memory of 20th-Century Conflict, organized by UCL, and held at the Imperial War Museum in London in September 2004. Further papers and drawings relating to these themes are available on my website: www.vortex.uwe.ac.uk

References

Alfrey, Nicholas and Daniels, Stephen (1990) Mapping the Landscape : Essays on Art and Cartography. Nottingham: Nottingham Castle Museum.

Buchanan H.D. (1892) 'Rules and Orders 1792' cited in Records of the Royal Military Academy 1741 – 1892. Woolwich: Cattermole, p33.

Diller and Scofidio (1994) Tourism of War, FRAC, Basse Normandie/University of Princeton Press, pp.116 - 177.

Foucault, Michel (1977) Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison. London: Allen Lane.

General Staff, War Office (1914) Manual of Map Reading and Field, H.M.S.O., London.

Green, A.F.U. (1908) Landscape Sketching for Military Purposes. London: Hugh Rees, London.

Gough, Paul (1995) Tales from the Bushy-Topped Tree': A Brief Survey of Military Sketching’, Imperial War Museum Review No. 10, London: Imperial War Museum / Leo Cooper, pp 62 – 73.

Hardie, Martin (1966) Watercolour Painting in Britain, Vol.1, The Eighteenth Century. London, Batsford pp 216 - 222.

James, Henry (1915) New York Times

Jones, David (1980) in Rene Hague (ed) Dai Greatcoat, London, Faber.

Junger, Ernst (1937/2003) in Susan Sontag, Regarding the pain of others, New York: Picador, pp 66-67.

Keegan, John (1976) The Face of Battle, London: Penguin.

Newton, William (1915) Military landscape Sketching and Target Indication. London, Hugh Rees.

R.F.C., (1916) Topographical Sketching in the Army, The Studio, pp 44 - 45.

Roberts, William (1974) Memories of the War to End all Wars: 4.5 Howitzer Gunner R.F.A. 1916 – 1918. London: Canada Press, pp 27 - 28.

Swofford, Anthony (2003) Jarhead. London: Scribner, p.135.

Illustrations

Figure One Panoramic Sketch with ranges for rifle fire, Barn Hill Wood, June 1915

Figure two Newton. Separation into Planes

back